The fate of the last king of Babylon is a mystery. Some kings of history are killed in battle or deposed in palace coups. Not Nabonidus. It seems that he just went walkabout.

In 553 BCE, Nabonidus left the famously decadent delights of Babylon and headed south into Arabia. By the time he came back, it was too late: his ancient kingdom had succumbed to the Persians.

Perhaps the least likely story about Nabonidus is the one you get in the Old Testament. In the Book of Daniel, the king goes mad and runs off into the “desert wilderness”.

Biblical writers have it in for Babylon and their kings: after all, they did enslave their people, inadvertently inspiring a Boney M hit in the process. But there is another reason why the Book of Daniel account is suspect.

Tayma, the part of the Nefud desert where the king ended up, was not a depopulated wilderness. It was, and is, an oasis, for centuries a crossroads of trade and a meeting point of civilisations.

This basalt stela showing Nabonidus, last king of Babylon, in an ornate headdress is now in the British Museum

Creative Commons 1.0/Babelstone

If Nabonidus wasn’t going to war, perhaps he was off on a little luxury shopping spree. Jade from China, spices from Oman, trinkets from Greece? A determined ruler could lay his hands on any of that stuff in Tayma ‒ and it appears Nabonidus did splash his cash on ancient homewares. A poem now in The British Museum records how he “made the town beautiful, built there a palace like the palace in Babylon”.

In Tayma today, artefacts with his name recorded in cuneiform have been found. Kate Hall-Tipping, expert in cultural planning, says the archaeological sites there “continue to yield discoveries that shine a light on the interconnectivity of ancient Arabia”.

Now this region is again becoming a hub of connectivity within Arabia and with the world beyond. Before very long, some two million tourists a year will be heading to this region, basing themselves in AlUla, 150 miles south of Tayma, another former stop on the ancient incense trail.

Robert Polidori/RCU

You may not have heard of AlUla, but global professionals in the worlds of archaeology, the arts, cultural planning and hospitality certainly have.

AlUla is in Saudi Arabia. This ancient land is going through a new economic and social revolution as it seeks to build an economy no longer reliant on oil. That dry economic fact has led to a much broader opening-up of this once closed society.

Since visas for the kingdom were made readily available in 2019, the region of AlUla has been attracting archaeologists, academics, tour companies, visiting artists and performers.

The inhabitants of modern AlUla are joining enthusiastically in a £11.5 billion project that is bringing opportunities to work and study and diversify their own, mainly agricultural, economy. The culture sector of the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU) estimates that tourism will ultimately account for 70% of local jobs – an extraordinary transformation in a country where tourism was until recently all but unknown.

Guests will also come for the landscape, the food, shows at the magical Maraya concert hall, large-scale art events such as Desert X AlUla and new permanent galleries in Old Town. But the biggest draw for every visitor to Alula will be the evidence left behind by the ancients.

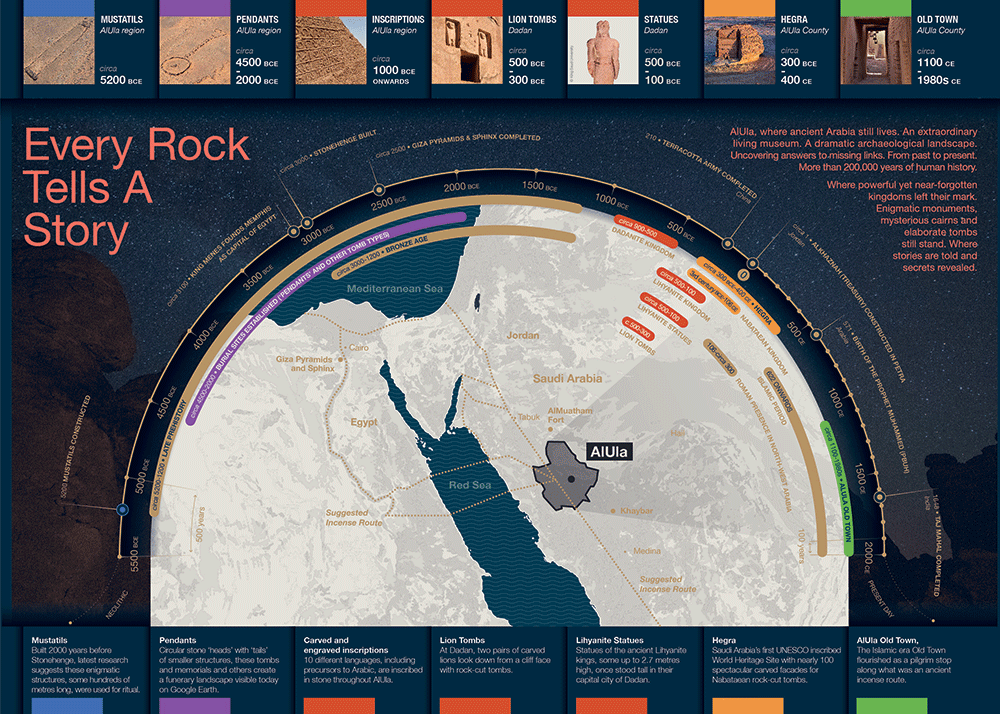

There is plenty of it. Archaeological surveys have so far documented 27,000 sites. To make sense of this vast landscape across time and space, five centres have been created: Hegra (Saudi Arabia’s first Unesco World Heritage Site), Dadan Heritage Site, Jabal Ikmah, AlUla Old Town and the adjacent Oasis. The heritage sites of Nabonidus’s Tayma and the oasis of Khaybar will soon be open to visitors too.

RCU

One image stands out. It’s in the heart of the Unesco-protected site of ancient Hegra: the Tomb of Lihyan, son of Kuza, standing, marooned like an ancient sandstone galleon, in the desert plain. Its view is iconic, unquestionably on a par with Machu Picchu and Petra, the Valley of the Kings and Angkor Wat.

It would be remarkable enough were this the only structure of its kind. But it’s only one of 111 rock-cut tombs among thousands in this vast necropolis, the silent city.

The tombs were created by the short-lived and enigmatic Nabatean empire which flourished around the time of Jesus Christ from its base in the hidden rock city of Petra, in modern Jordan.

Videographer Charlie Wharton

But before we get to the Nabateans, we need to go back much, much further. Let’s start with a picture of a cow. It’s not the best picture of a cow you’ll ever see. But it’s one of the most significant. It was carved on a rock wall around 7,000 years ago.

According to Rebecca Foote, director of archaeology and cultural heritage research at the RCU, it confirms that a major turning point in human history, from hunting to herding, happened in AlUla much earlier than previously known.

Various kingdoms came and went. It was the Dadanites, or Lihyanites, who succeeded, establishing a small but wealthy and resilient empire that would last for seven centuries until 24 BCE.

Videographer Charlie Wharton

We are spending the morning in the Lihyanites’ main city of Dadan, a matter of kilometres north of AlUla Old Town.

Jonathan Wilson, collections manager at the RCU, cut his curatorial teeth at places like the Black Country Living Museum and Plymouth’s City Museums and Art Gallery. But today he is acting the part of a middle-class Dadanite citizen in about 400 BCE.

We are looking at a rubbly landscape of low walls, dominated by a sandstone cistern and the remains of what is almost certainly a temple.

His words transport us to a city that had been going strong for as long as Rome and Athens have today. His citizen is trading in frankincense and myrrh – luxury commodities then, as they still would be when the three kings made their journey to Bethlehem centuries later.

Our trader knows Greeks, Egyptians and Babylonians; he has perhaps handled jade from China. His city is presided over by the spirits of the dead: their lion tombs are cut high into the rock face, as they still are today.

The region around AlUla has played host to many civilisations ‒ and even the very earliest have left mementos that can be seen today

RCU

RCU’s culture sector brings together many specialists from around the world, such as Hall-Tipping and her colleague Leila Chapman, who work closely with Saudi colleagues from AlUla and elsewhere.

“The majority now live and work together in AlUla,” says Kate, “to bring the world of visitor experience, cultural development and historic significance together”.

The descendants of our Dadanite trade lived, as his own ancestors had, largely at peace with other civilisations – trading partners, rather than warring states. But in 24 BCE, the Nabatean was a kingdom in a hurry. Having established the fabulously wealthy Petra, this once-nomadic Bedouin tribe decided they wanted the southern incense trade for themselves.

They defeated the Dadanites and moved their capital north, bringing in their superbly accomplished masons to create that silent city of rock tombs.

Videographer Charlie Wharton

At the rock library of Jabal Ikmah we meet a rawi – one of the storytellers who guide visitors around these ancient sites. Amal, a small, slight figure in black abaya, veil, bush hat and silver trainers, perches herself on a boulder, her voice echoing around the canyon as she describes the sacred carvings and records the Nabateans, and others, left here. Amal says her job is “something nice. It makes you share your culture with different people”.

AlUla is also a journey through the deep history of the Arabic language. If you want to hear that language at its most animated, end your own journey through time in AlUla’s Old Town.

The Romans supplanted the Nabateans, declined, fell. With the Muslim conquests came centuries of quiet stability – although the World Wars of the 20th century did affect people, even here. In the north, the Ottoman empire’s grand project, the Hejaz railway was destroyed by Arab rebels, among whose number was a maverick British army officer called T E Lawrence ‒ “of Arabia” fame.

The abandoned Old Town from above, before renovations began

RCU

By the Eighties, the remaining citizens abandoned the older houses. But instead of ending up as piles of rubble and broken walls, AlUla Old Town is enjoying an extraordinary resurrection. The abandoned houses have been renovated into art galleries and cafes. Visiting artists from around the world have their studios in the upstairs rooms. Saudi artists display their work in the houses and the gaps between the houses (not much fear of rain here).

The former girls’ school has been turned into a thriving vocation centre of traditional crafts supported by our own Prince of Wales.

AlUla never was a silent, desolate, remote place. But now it’s as thriving and busy as at any time in its history. What treasures and symbols will this civilisation leave for future explorers to find?

For more information on visiting AlUla or to book a trip, visit experiencealula.com