In the corner of the pottery workshop at the Madrasat AdDeera there are three sacks of soil: and very useful and precious soil it is, too.

It doesn’t rain very much here in AlUla: we are in the north-west of the Arabian Peninsula. In the very wettest months (December and January), there is at most a 2 per cent chance of rain. You might get 20mm of the stuff.

Hamad Homiedan

But if the heavens do open, even a little, class is suspended and students race out to the desert with sacks and buckets.

“When it rains, everyone goes to the desert to gather the clay,” says Hamad Homiedan, arts and design centre lead at the Madrasat AdDeera. “And then they create these beautiful pieces, each one unique and handcrafted from scratch.”

There is something eloquent about those sacks of now-dry desert earth. In the alcoves and on the shelves of the Madrasat, and in its small shop a short walk away in the old town, you see the vases and pots made from that clay. Some of the designs were first seen in the ancient empires that inhabited this place 2,000 years ago or more.

As a visitor, a tourist, of course you want to buy something when you come to a city such as AlUla. That goes for just about everything – the textiles, the glassware, the jewellery here. When you travel, you often see the same stuff everywhere, ‘handicrafts’ mass-produced in South East Asian or Kashmiri factories.

Then you happen across a place like this, where what you buy isn’t just a souvenir, not only a lovely thing in itself but a unique journey through time in miniature – and where the money from what you buy goes to the local people who made it.

The Madrasat opened as a girls’ school here in rural north-west Saudi Arabia in 1970. But by 1999, this functional, airy, whitewashed building had been abandoned. So had many of the streets and houses around it.

It happens. People find more modern and convenient places to live. The infrastructure they used to rely on has no further purpose. Houses, and the school, lay empty. The only sound was the desert wind.

But this isn't just any remote desert town.

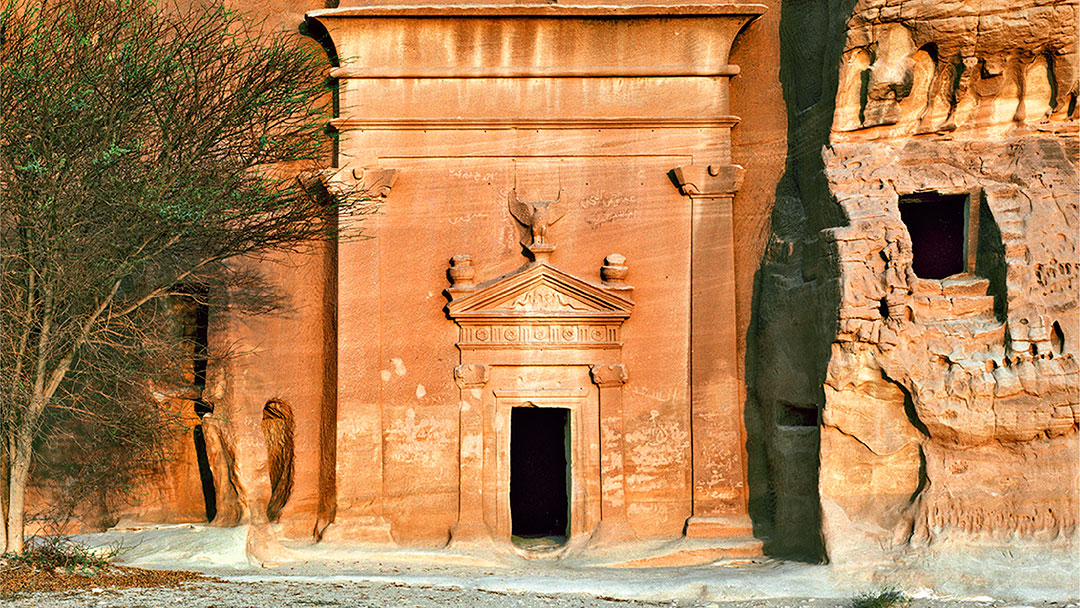

AlUla came to be because of the oasis and the traders who have followed time-worn routes, from Damascus to the north and the great Silk Road, and Medina and the Red Sea coast to the south, where precious goods would be sailed to India and China. The architectural heritage that those kingdoms and their traders left is astonishing, most notably – but far from uniquely – in the Nabatean tombs of the Silent City, Hegra.

One of the “astonishing” ruins left behind by the Nabateans

Robert Polidori

The archaeological sites bear comparison with Baalbek, Tyre, Petra, Palmyra and the other architectural treasures of the region's pre-Islamic past. But unlike those names, AlUla is not yet a familiar one. That past was buried during Saudi Arabia’s ‘closed’ decades of the 1980s and 1990s: there were no tourists or visiting archaeologists – even well-travelled Saudis had little or no experience of AlUla

That has now changed, and changed dramatically. The £11.5 billion plan to transform AlUla into a world centre of tourism, where contemporary and ancient art co-exists with traditional craft, is well under way. The masterplan, appropriately, is called a Journey Through Time.

Much can be lost as the centuries slip away, including those traditional crafts. The Madrasat reopened as a school for local people to learn those skills anew. But this is not a kind of night school where people take up new hobbies as an alternative to watching Netflix.

The 70 students – or artisans, as Homiedan prefers to call them – are here to make the money, start their own businesses or supply the growing local demand for products that are functional, beautiful and, above all, local.

Wander into the weaving room and a dozen women sit cross-legged, plaiting straw and chatting. It’s a friendly, relaxed scene that belies the hard commercial activity going on here. These artisans will sell their work – often on the very evening they produce their baskets, pots and bracelets – in the old town.

“The primary objective is to empower the local community in craft making and help them earn a livelihood,” says Hamad.

The friendly, relaxed atmosphere in the weaving room belies the hard commercial activity going on here

Today in the Madrasat, things are a little different. There’s a visiting artist here. Catalina Swinburn was born in Chile, lives in Buenos Aires and has a studio in London. Today, she is demonstrating her own unique brand of weaving, sculpture, textiles and art.

Twenty artisans, all women, sit around the table. Catalina – Cata – hands out small squares of paper cut out from an old book of maps. Minutes later, everyone is heads down plaiting the squares: it’s a cross between weaving and origami.

The students get the hang of it quickly and chat away as they work.

“What do they think of this?” I ask one of the tutors.

“They’re thinking how they can make money out of it!”

Western visitors are not an unusual site here. They include the Prince of Wales and his cousin, Lord Snowdon, perhaps as well-known as David Linley, founder of the eponymous fine furniture company. They are founder and vice president respectively of The Prince's Foundation School of Traditional Arts, a body devoted to preserving traditional crafts globally and rediscovering lost ones.

David Linley, Lord Snowdon

Lord Snowdon tells me: “We’ve taken stock and asked, ‘What am I leaving behind? What am I going to hand down?’ It’s wonderful to see the resurgence of young people especially wanting to learn old skills again.”

He was also pleased to see the sacks of dirt.

“Some of the modern colours they were using were rather garish. One of the teachers asked, ‘Why don’t you use the colours that are here?’ They’ve got rather marvellous paint colours from the stones they find around there”.

The Foundation set up Turquoise Mountain, an agency designed to make a link between that noble aspiration of conservation and preservation; and producing goods that have a market and earn money.

Harriet Frances, Turquoise Mountain

Harriet Frances from Turquoise Mountain says that combined mission is going well. “The Madrasat has been very successful. Something will be made here at 11, it’s in the shop at 3 and sold out by 6.

“They have a training curriculum, but most of their work is commercial orders – hotels, stores, restaurants, in AlUla or internationally. The income is significant.”

The artisans are paid to attend – enough to cover the costs of transport for those in outlying areas. But when a piece is sold, they get up to 90 per cent of the proceeds.

In the Masterplan for AlUla’s development, the Madrasat is one of the ways that local people, and particularly women, are being empowered.

The Royal Commission of AlUla promotes a social development model that favours the ethical employment of women, from artists to tour guides to local farmers producing peregrina oil, a natural product from trees that grow in the harsh desert environment, which is used to make organic skincare products.

It’s getting to the end of the school day and Cata’s students have finished. The work they have created is a thing of magic: a paper ‘map cloak’ woven from pieces of maps, fragments of the planet.

“I wanted them to know,” says Cata, “that their knowledge is now visible on the map.”

It is visible, too, as we walk through the streets of the old town. This once deserted place still has no traffic – of the mechanised kind. Hundreds of people park their cars just beyond the Madrasat site and wander into town to visit the galleries, dine, drink tea and browse.

In the Madrasat’s small shop, tapestries, cushions, those earthenware pots and even tote bags are arranged on wooden shelves. The colour and the designs have an ancient simplicity yet a very contemporary quality, too: you sense that time, thought and patience has gone into the making.

On the street, as the sun sets over Harrat Uwayrid, the great volcanic plateau that overlooks this fertile canyon, there is a gently festive feeling in the air as families and couples – but not, as yet, many Western tourists – stroll by.

“It is an incredible development,” says Al Joud. “No one knew what AlUla was. Now everyone is interested.”

For more information on visiting AlUla or to book a trip, visit experiencealula.com